In a nutshell

The three stereo recordings below are of Mozart’s piano quartet K478 (1st movement). All video is identical. The first two have sound images dynamically adapted to the video image. The first has a moderate adaptation, and the second has more significant changes to the audio field so that you hear instruments in the same part of the audio field as the video. The third recording is a regular fixed stereo sound provided for reference. Please wear headphones or listen with real stereo speakers well positioned to the screen’s side. We suggest listening in the following order:

- UPDATE (22/03/2021): 45-second demo with three stereo images is here.

- Full-length video with moderately adaptative audio is here (extract here).

- Full-length video with strongly adaptative audio is here (extract here)

- Full-length video with regular fixed stereo audio is here (extract here)

To take this project further, one option could be to produce a live concert (not necessarily classical music) with a similar low-tech approach. Another would be to embrace more sophisticated technology such as NextGen Audio (NGA) like MPEG-H, Dolby Atmos, or DTS:X and film in 8K. We could create multiple versions in a third option, perhaps using some AI or specific metadata to create a personalised edit and mix.

Another area to explore would be using track delay to create a sense of spatialisation within the stereo mix.

A bit more detail on the genesis of this project:

Working on UHD technologies, especially since I joined the Ultra HD Forum over five years ago, I have often been excited, my eyes and ears blown away by impressive demos of the latest and best audio and video technologies. Vendors like DTS, Fraunhofer, Harmonic, Sony, Samsung, Dolby, and others are good at making such demos. But I’m a geek, and it’s the technology that vendor demos show off to which I respond. New technologies serve no purpose; they should help filmmakers and other artists capture emotions and tell stories better. It is noteworthy that Dolby has been energetically pushing ATMOS with some renowned musicians.

When I have the opportunity, I often present new UHD and audio technologies, including 8K and HDR to friends in the movie business in France. It was, at first, a mystery to me why they often wouldn’t engage. I have identified at least one reason for this resistance. Many filmmakers had their fingers burnt in the transition from analogue to digital as the first generations of technology made it harder to capture their artistic intent. I was rarely able to convey that almost all newer technologies can also mimic the older ones once in the digital domain. So, if you want the granularity of 2K instead of 4K, more limited colour space, or a reduced dynamic range, that’s all easy to achieve in postproduction.

This technology vs art issue has been obsessing me for a few years. When presenting UHD to many artists, I felt as if I were someone in a world with only two primary colours, trying to explain to artists what they might gain by adopting the third one.

It is essential to avoid the trap that any shiny new technology sets. When, for example, digital music production came onto the scene as early as the eighties, many became obsessed with sequencers, MIDI, and heavily overused repetitive rhythm boxes.

The COVID-induced sanitary situation woke me from my slumbering thoughts. So many of us miss the part of “being there”. What if there were a way to use today’s readily available technologies better to tell the story of a concert or maybe a play?

So, the video we made is the story of a concert delivered using only HD resolution and regular stereo sound. It was a few weeks of planning, a day’s shooting, and a few weeks of mixing and post-producing.

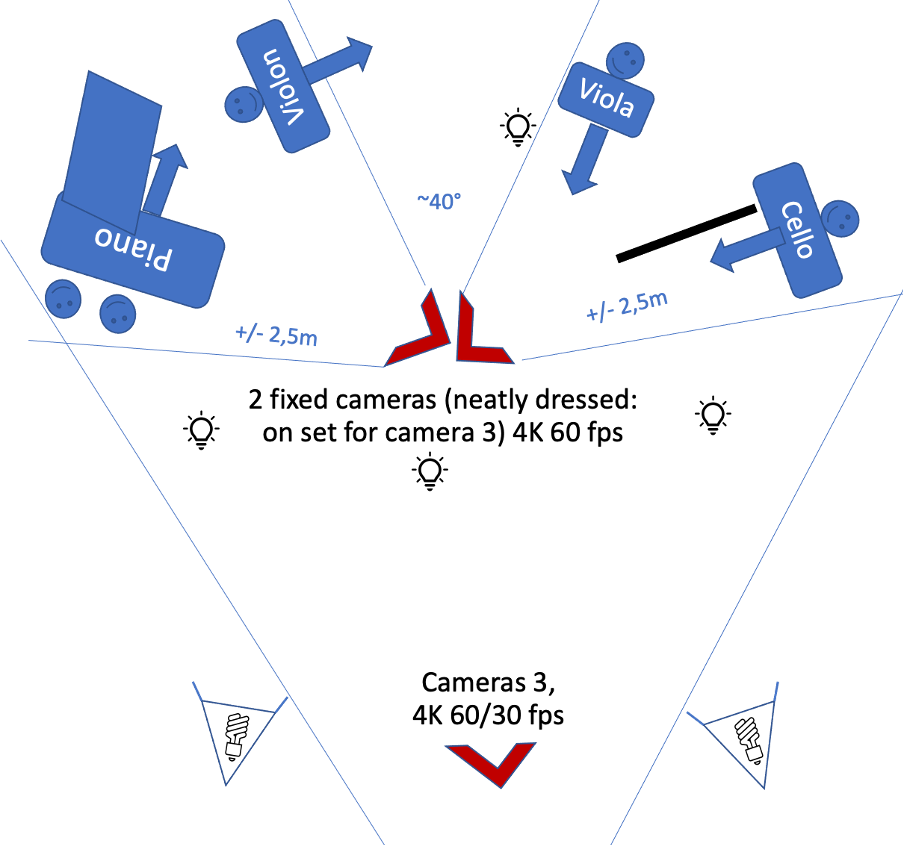

The three iPhone cameras are on tripods and all within a small space. So, you get to experience the concert as if you were there. We filmed in 4K and produced in HD, so all camera movements are post-produced.

A professional sound engineer did all the sound mixing (see credits). We adapted all the stereo sound images to the camera angles. We didn’t use any new next-generation audio technology, just plain vanilla stereo. To keep it low-tech and straightforward, the only effect used in postproduction was panning, i.e., controlling each audio input's left/right mix. So, when an instrument is on one side of the image, you hear it from that side. We refrained from adapting the volume on any track or changing any equalisers (there is only a simple one to enhance the cello).

Using so many panning breaks with current mixing rules because we lose much of the field depth. The first version in the URLs listed above, where audio adaptation is moderate, is the best compromise, and I am ready for the sound mixing community’s wrath. Early stereo recordings often used extreme panning. Today, there are still recordings with one instrument coming mainly from one of the two stereo channels, but these are rare, and the stereo field remains fixed during the recording. In our eight ½-minute video, nine different sound fields are used about 90 times.

If you find this demo convincing, imagine how much more advanced technology like NGA and 8K could achieve.

You will feel immersion if you wear earphones or listen on a sound system with clearly separated left and right channels (either side of your TV or video screen).

The musical director — and not me — had the final say on all cuts. Artistic intent is our unique driver, not showing off the technology. We humbly hope this is one of the ways Mozart would have liked you to experience his music. We have made artistic choices and understand that others may want to experience this work of art differently. Perhaps we’ll go for a piece with fewer intricacies leading to fewer interpretation choices in a future recording.

We are looking forward to your feedback.

Musical credits

Mozart Piano Quartet K478, first movement

- Piano Ionel Streba

- Violon Bertrand Aimar

- Viola Kyoko Yamada

- Cello Hélène Billard

Audio and video credits

- Produced and shot at Hôpital Rothschild Auditorium by Ben Schwarz

- Music director Bertrand Aimar

- Audio equipment Pierre Gauthier

- Recording engineer Arnaud Chu

- Audio mix engineer: Rémi Nicollet

- Audiophile consultant Laurent Appercel

- Postproduction advice Thomas Perin (also Cyril Zajac and Chris Harless)

- Thanks also to Ecole Polynotes