This blog has been brewing for several years. As I’m locked down in rural Essex (UK), the global pandemic brings a sense of urgency to my dilemma. The whole world had never just stopped before in our lifetimes. As I write, I’m fortunate not to have been personally affected by the tragedy of the loss of life, for which I am very grateful.

As many have noted, the global situation is also an opportunity for us to question the very structure of our societies. As candidly as possible. Clean air, unpolluted skies, and strangers looking after each other have been the few positive features of this pandemic. But above all, it has become apparent that we could afford to pay to save the planet if we chose to. Some things have turned out to be more important than GDP and short-term economic growth.

Many of our mainstream politicians are clamouring for us to return to where we were as quickly as possible. But society as a whole might no longer want that.

What are the personal questions for those of us who love technology and whose chosen career is to promote it? Is now the right time to reposition ourselves and reconcile our aspirations with our actions? Let’s call this the Technology Enthusiast’s Environmental Dilemma or TEE-dilemma.

In this personal post, I’ll attempt to address the issue of making peace with my bewildered self in the different universes I inhabit and, hopefully, find some commonality between them. I’m a geek technology consultant and video, innovation and Blockchain writer. I’m also an active member of the French green party. I want to understand better how I might be able to reconcile the following:

- Helping to invent disruptive new digital services that we hope people will find useful

- Assisting vendors and operators in deploying more and more powerful networks to distribute content ever faster

- Promoting bigger, brighter, better video and TV technology

- Evangelising on the subject of often energy-hungry blockchain technology

- Keeping buying the latest i-gadgets for myself

- Campaigning for the green party

I became a geek in my early twenties. I’m now 55, so I’ve fretted about Moore’s law for over 30 years. That’s the one that said computing power doubles about every 18 months; it remained valid for decades. None of my computers ever reached the age of three for all that time. For over twenty years, I’ve also kept my mobile phone up to date, rarely letting it get more than a year old. I’ve provided strategic advice and consulting to startups and multi-billion-dollar operators alike. I’ve written dozens of business and technology white papers and hundreds of blogs on better ways of delivering video, and more recently have written about Blockchain.

Privately, I’ve also been a green political activist for 30 years.

I’m finding it harder and harder to make all this square up.

My parents were progressive, and although they were not very interested in technology, I grew up thinking that high tech constitutes Progress (with a capital P).

OK, so what constitutes technological Progress?

Wikipedia says Progress is the movement towards a refined, improved, or desired state.

In the early 1980s, when I was a teenager, my parents were already active in the green movement. Before the paper had an environmental correspondent, my father covered environmental issues in The Guardian. I remember a chat with the ecologist Teddy Goldsmith when I questioned him on what I perceived to be the Green’s scorn for “Progress”. I was travelling in the boot of our station wagon, and he was in the rear seat — someone even more important must have been in front. He turned around, looked at me kindly, and said, “You know, Ben, as ecologists, we don’t believe in returning to the treetops. We embrace progress!”. Of course, we then spent the rest of the journey arguing what Progress was, measuring happiness rather than growth etc.

That moment has stayed with me ever since. When does Progress have a capital P, and when is it just ephemeral trivia? Any technology can indeed achieve both and everything in between.

The effectiveness or impact of something new is not necessarily correlated to its usefulness — social, environmental or otherwise.

If you introduce the hammer to a society that doesn’t have one, its people will likely learn to build better houses. At the same time, and probably quickly, someone will also use one to crush another person’s skull more effectively. Progress is neither good nor bad per se; it’s what we do with it.

An example of a useful disruptive innovation?

Like many innovations, mobile text messaging or SMS came about by accident.

WhatsApp is an example of the continuation of that disruption in personal communications. The profound change came from opening up a new communication channel that was real-time (like a phone call you receive at the same time it is made) and asynchronous (like email, that you answer at your leisure). People could communicate in numerous ways that they couldn’t access before. Proof of the pudding is visible in how even tech-phobic people managed to use SMS messaging before the invention of the T9 keyboard. Remember when you needed to hit the ‘2’ key three times to get a ‘C’? Who recalls under which number represented the space bar? Yet text messaging swept the world because it gave us something we didn’t have before and answered a need to communicate asynchronously in real time. We want the receiver to have the information at once when we send messages. When we receive messages, we want to control when we acknowledge or answer an incoming message. SMS leverages the benefits of real-time communications without enslaving us to their demands. Surely that’s the kind of Useful Progress Teddy Goldsmith meant?

Here my TEE dilemma is exacerbated by the observation that an element of Reaganomics-style “the market always knows best” helps determine what constitutes Progress. Until the market spoke, the paragraph above could only be conjecture.

Trade-offs in the Age of Greta Thunberg

The SMS example showed that people are prepared to learn a ‘barbaric’ user interface when they gain something they consider worth that amount of effort.

But such a trade-off is very complex to understand with as many rational (e.g. time-saving) as irrational (e.g. ‘feeling good’) criteria.

In 2020 a new criterion for such choices, that is, both rational and irrational, has entered our lives. As a society, we are starting to take environmental impact seriously. Well, many of us are.

Purchasing an electric vehicle illustrates that mix of rational and irrational behaviour. If you’ve researched, you’ll know that today’s electric or hybrid cars mostly have a more harmful global impact than an optimised traditional vehicle. That is partly due to the inefficiency of battery production and disposal. Yet we live in a consumerist capitalist society. So, we know that the only way to get to more efficient electric cars is for the industry to make money from them today. That ensures that they will continue research for tomorrow. As with the good-vs-bad potential uses of the hammer, the ‘greater good’ argument becomes even more apparent.

SMS would never have taken off if it had only delivered an incremental improvement rather than a unique and disruptive communication method.

We must make constant trade-offs as we face our own TEE dilemmas. As we see repeatedly, this can involve accepting a less-than-ideal project as long as it’s a stepping stone to something better.

CDNs represented Progress; do they still?

Content Delivery Networks, or CDNs, can enable websites and online services to offer more engaging content. In the early Web, images and audio became part of websites, and CDNs solved the problem of having to take many minutes to load. They also allowed millions of people to access the same content simultaneously. Today, much more challenging things are available online for which CDNs are needed — for example, very high-resolution video.

CDNs have caches (usually hard disk space on specialised computers) that store content closer to users, so the data doesn’t need to travel worldwide. For the most popular content on a service like YouTube, it makes sense from an energy perspective to add caches worldwide. These devices are typically within your Internet Service Provider’s network. Such an approach offers a more sustainable way to deliver the ever-expanding content that many will want to watch. So, well into the future, there is a level of CDN development that we can consider as Progress with a capital P. However, once the necessary CDN infrastructure is enabled, the CDN ecosystem continues to find other ways of growing sales. That’s still the only way we know how to run high-tech businesses.

Issues that vendors are working on include making load times even shorter and reducing the delay for live streams. These are genuinely cool features for consumers. Are they “nice-to-have” or “must-have” features? To what extent do they, like the SMS, enable something that wouldn’t otherwise be possible? Reducing stream delay avoids hearing “GOAL!” screamed in the neighbour’s flat half a minute before you see it. This “issue” is a real problem once every four years during national team games in the World Cup. Beyond that case, is reducing the delay below 10 to 20 seconds Progress or mere convenience?

Of course, there will always be some niche use cases like live interactive talk shows where low delay times become a “must-have”. But otherwise, the jury is still out in most situations.

In the meantime, to continue to improve user experience, new infrastructure is being disseminated around the globe to be ever closer to where people consume content. We started doing this in a few dedicated data centres, then moved to the Cloud, which physically exists in hundreds of places. Now we are heading to the Fog, which is also referred to as edge-computing. Cloud computing infrastructure is typically in large data centres, often run by companies like Amazon or Microsoft. In contrast, Fog or Edge computing happens much closer to your home, for example, in a cabinet in your building or on the kerb nearby.

This trend creates significant power requirements. When you search online for “Power consumption on CDN”, the top results are all from academic research. CDN vendors haven’t yet significantly invested in this space. I guess because they don’t see it as good for business. They are mistaken, and this attitude needs to change. The ability to recognise where disruption would be desirable is essential. Netflix showed us over the last decade that completely disrupting their DVD distribution business with Internet streaming was necessary. Providing the platform for that disruption was even better, as the Blockbuster chain found out too late.

Another example is with big oil conglomerates for whom the success of renewable energies seems undesirable. Yet the biggest oil companies in the world are investing massively in renewable energy. If you’re going to lose a limb, it’s better to remain in control and choose the surgeon yourself.

CDN stakeholders could embrace energy conservation by creating an eco-friendly label.

Note, for instance, that peer-to-peer CDNs that only use users’ spare capacity are, although not energy-neutral, significantly more friendly to the planet.

For example, we must be careful to avoid greenwashing the issue by just saying that ‘we build hardware with recyclable materials’. That’s not enough. We need to find new models.

In the CDN arena, I’ve heard ideas about letting end-users choose the level of service they want in real-time, and paying for it. That could be a start. An associated idea would be to certify a video’s “green” path through the Internet, perhaps using blockchain technology.

Is Internet streaming or broadcasting better for the planet?

Ten years ago, working with another independent consultant, I compared the energy efficiency of different TV distribution technologies: terrestrial, satellite and Internet. We did some preliminary work and then tried to sell a study to any stakeholders involved. We couldn’t even find the right person with whom to talk. If you’re wondering how the energy footprint compares, expect the usual “it depends” answer. You’ll find different studies coming to diametrically opposite conclusions. It depends on too many factors to provide a simple answer: size and geographic spread of viewership, number of concurrent streams, delinearisation, decoding standby power consumption, etc.

Please let me know if there are any takers now; I’d love to take another stab. Relevant data should be available to regulators and consumers.

And do we need ever-better video and screens?

As a cinemagoer, high tech always attracts me to the movies. I have even been to the cinema a few times, not because of what was showing, but to experience the newest or largest screen in Paris. I’d happily cross town to see a movie with next-generation immersive sound, even if the same film played at my local cinema with plain vanilla audio.

I’m an active member of the Ultra HD Forum, an industry group that promotes the next generation of video technology. It may be part of my job, but I do it because I love it.

TV screens have grown by an average of an inch per year in most markets. To cater for the latest colour and contrast capabilities, the brightness and hence the energy consumption of screens have more than doubled over the last decade.

To decode the newest video formats and run apps, the processing power of TVs is also growing fast. A high-end television has little to envy in a computer.

Video is one of my worlds. I always took it for granted that all its innovations constituted Progress.

I consoled myself that although devices were getting more powerful, hardware was getting more efficient. Ultimately, at least from the energy consumption perspective, we weren’t on a worsening curve.

As TVs get more powerful, they deliver more services, and even if they do so with improving efficiency, the result will still be more energy consumption.

Leaving aside the carbon footprint of making them, the latest TVs can be very energy-hungry during peak usage. Such occurrences can happen when all of the screen is very bright, or the TV is working hard to decode a very highly compressed video. However, the set will also be very energy efficient in other circumstances.

Whether these new energy-hungry video technologies become the right kind of Progress depends on the artists in the cinema and TV production worlds. They would need to understand the unique capabilities like high dynamic range with more colours and contrast, much higher resolutions, screen refresh rates and immersive sound. When they can, they would need to use these new features as an extended or even new vocabulary to enhance their storytelling. This new language also needs learning for live events and sports production. Despite having four times more resolution, today’s 4K football matches using the same shots as HD don’t benefit from the potential of the new, more immersive storytelling that would come with wider angled shots.

Improvements in the latest fancy TVs and associated technologies will be justified, and the Progress they represent will deserve a capital P once artists start talking on them with the new languages of higher resolution or contrast, using immersive sound to say things that couldn’t otherwise be told.

Can Blockchain change the world without consuming so much energy?

In 2016, my sixteen-year-old son suggested we build an Ethereum mining rig. I didn’t know what he was talking about, but we started researching it so that less than a year later, we were mining cryptocurrency. The extra hundred euros a month in electricity cost seemed like nothing. We were generating a profit, and I got increasingly enthusiastic about how the underlying blockchain technology would improve the world. Like most blockchain and bitcoin newbies, videos by Andreas Antonopoulos (aanatop) on the evil banking system truly inspired me. Of the countless stories that fired me, I remember how cryptocurrencies would fix the problem of migrant workers that send their earnings home. They could (and still can) spend up to a month of their yearly incomes on a remittance company. Crypto can knock that 9% fee down to almost nothing.

Being of the X generation, I feel we’re the true digital natives because we tasted a pre-internet world before building the current one. I have always been fascinated with the concept of a digital entity. As I write on my computer, the words already exist in a few different places: on the bitmap of my screen, in the RAM used by the word processor and in caches and temporary backups. Digital entities have never really existed as physical ones do. There are only copies of them. Even if there’s only one copy left, it still has the properties of a copy. It’s always ready to be duplicated ad infinitum and only rarely and temporarily exists as a unique copy. Thanks to Blockchain, now is the first time you can truly own something digital because it is finally unique. The impact of this will take many years to permeate through the whole of the Internet and our lives, but there will be a before and an after. One day we’ll wonder how we ever put up with spam or all the digital fraud surrounding us. One day we could own part of a digital piece of art. With the tokenisation of the economy, we can invest in just that part of a company that interests us. Even as small shareholders, we’ll have an influence.

So that’s just the tip of the iceberg. I became pretty obsessed with it a few years ago, tirelessly explaining Blockchain and how it would change society to anyone who would listen. My apologies if you were one of my early victims. As Bitcoin hit 20k in December 2017, I thought the world had understood too.

We saw people become millionaires or even billionaires overnight. But money corrupts, and if we’re honest, most enthusiasts saw our genuine passion for the technology tainted with at least a small desire to get rich quickly.

I was lucky to find a company in 2018 that, although seeded with some of those riches, was focused on delivering Blockchain’s promise. So I got my head under the bonnet. I’ve mainly been writing about mobility, energy and fintech, and I still need to get my hands truly dirty on implementation projects.

I do not doubt that Blockchain will one day deliver on its incredible promises, even if I can’t say when. Of the many areas Blockchain promises to change, perhaps the most appropriate when discussing my dilemma is how energy distribution can be improved. Blockchain’s secure identity management enables marketplaces where consumers can produce or resell. An intelligent electric car of the future will share excess power back to the grid during peak consumption, or with another vehicle in need, during a traffic jam.

Cryptocurrencies like bitcoin are just one of the countless blockchain applications. By far the most valuable, Bitcoin uses a technique called proof-of-work, where energy expenditure is crucial in bringing security. Enthusiasts go as far as explaining how this will benefit the planet. They will point out that bitcoin mining can be set up to use spare energy that would otherwise go to waste. Bitcoin could even underwrite new renewable energy initiatives where capacity doesn’t always match demand. So, we’d only do the energy-consuming mining when the sun is shining, or the wind is blowing, and we don’t need all the power generated. But those arguments feel like an afterthought, and as I wrote this in early 2020, the global energy consumption of the bitcoin network is equivalent to that of Austria. My TEE dilemma has resolved itself on this one. I believe that bitcoin has to move away from current proof-of-work algorithms or otherwise lose its pre-eminence to coins that use less energy-centric approaches to security. This reservation is also valid for some other cryptocurrencies like Ethereum.

As we are still looking for ways out of the COVID lockdown, Blockchain promises to solve the people-tracking challenge without compromising privacy and securing supply chains for PPE and other supplies. So far, though, despite some valiant efforts, the open-source blockchain community hasn’t been able to respond fast enough.

And so, after this, what might change?

Even if we return to our previous ways with a vengeance once the coronavirus pandemic is behind us, something will have changed. The most eager and venal decision-makers will have heard the birdsong during the epidemic and felt the renewed environmental aspirations themselves or at least through others. They will be more open on an issue like Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) if nothing else. Social responsibility has continuously been on my radar from a personal perspective and as a political activist. But so far, from a corporate angle, I’ve only seen real engagement episodically.

[MY BRUSHES WITH CSR]

In my early career in IT, I was briefly a trade union rep. It was the early 90s, and I was trying to persuade the CEO to commit some meagre resources to a social issue we were impacting at the time. He answered that our job as a company was to maximise profits, so we’d pay enough taxes so that the state could fix that problem — whatever it was. That answer was un-challengeable then. Even before the pandemic, such attitudes were questionable, but after COVID-19, they most definitely will be questioned. In liberal, free-market societies, beyond greed, there is a whole belief system that growth and profit are the only two real drivers for companies. Anything else is only there to serve those two.

A decade after that incident, I was working for a major Telco. In the early noughties, when CSR had only just left the confines of academia, the voluntary sector and a few small companies began to knock on bigger corporate doors timidly. The iconic Ben & Jerry’s (which reserved 7.5% of profits to fund community projects from the mid-80s) had just been sold to Unilever. I was tasked with initiating our approach to CSR. The Cloud and its energy-hungry servers were not yet an issue, and we didn’t see Telecom’s carbon impact as significant back then. After much soul searching and advice, we rightly concluded that our mission statement moving forwards would be to provide access to information and services. In that context of “information super-highways”, trendy at the time, we thought about CSR as if we were a highway operator.

What was their responsibility to society, beyond the safety concerns that are taken for granted? It can’t be their responsibility if a road took you somewhere you didn’t intend to go. Is that even anyone’s responsibility? What if the road operator knows someone intending to commit a crime takes their highway? In the borderless world of the global internet, there are no laws to determine right from wrong or even what a ‘crime’ is. So, with a worldwide and timeless view, I asked what we could identify as universally wrong. Over time and space, the only issue that consistently came up was in the area of sexual exploitation of one’s own children. Nothing else fits the bill. Needless to say that after months of effort on this, my report and suggested actions simply got buried.

‘CSR manager’ will be a more desirable job in a post-COVID world. I’m told by a US-based specialist that her activity is skyrocketing as businesses scramble to bring social and environmental responsibility into their blueprint rather than a mere footnote of their strategy.

COVID-19 has brought the age-old personal dilemma of doing the right thing versus whatever brings more immediate rewards powerfully into focus for individuals. Organisations, including governments, seem to be affected too. My TEE dilemma has become a gaping hole consuming more of our collective psychological energy.

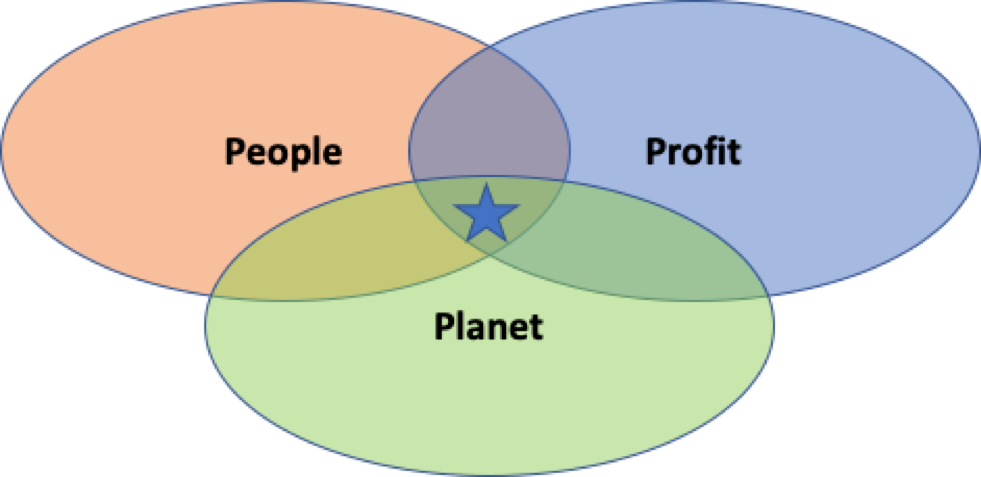

Green parties the world over have been grappling with this since the 1980s, adding the environmental dimension to the society vs economy debate. Teddy Goldsmith’s insistence that Progress is mainly good is echoed in more recent ideas about Profit not being intrinsically evil either. In one of his presidential campaigns, Obama sowed the idea that an environmentally friendly investment could create jobs and wealth. Green Parties often push the belief that becoming a world leader in energy conservation creates jobs, re-sellable expertise and wealth (yes, they even say that word sometimes). The Green New Deal is rooted in the workings of free capital markets.

Whatever posture they take in the short term, few greens, until now, have been revolutionaries. They have mostly listened and made compromises. Despite being otherwise radical, the XR movement follows social distancing more than most. But suppose our cherished liberal democracies don’t find a way to tackle global warming and our societies continue to polarise. The green movement will be forced into more profound radicalisation in that case.

Sustainable accounting has been promoted for over a decade to reach a sustainability goal (the star in the diagram above). Some states like France, for example, have started to introduce CSR (called RSE in French) into law.

We all know how to do sound business to a certain degree and aspire to this. We all care about the environment to some degree. So, we can all empathise with the difficulty of finding a balance.

A post-COVID-19 world (or maybe for a few problematic years, it’ll be an ongoing COVID-19 world) will leave less room for any corporate head-in-the-sand attitudes.

I’ve stuck my neck out a bit in this post. I sincerely hope it won’t upset any of my trusted clients but will be of genuine interest. I no longer want to bite my tongue when asked to develop or promote something that is a definite step backwards regarding social or environmental impact. Now I will say what I think and offer to explore how to reduce that impact where possible. Still, I’ll always be fascinated by new ways of solving problems and will remain a tech enthusiast — hopefully, an increasingly wiser one.

You must log in to post a comment.